The Book of Delights Read online

Page 2

(Aug. 24)

5. Hole in the Head

I love weird vernacular sayings that roll off the tongue and most likely have an interesting lineage/etymology/history. I can’t think of one right now, but you know what I mean. Well, here’s one: “I need x like I need a hole in my head.” This means “I do not need x.” I need to be fired like I need a hole in my head. I need this cancer to resurface like I need a hole in my head. I need my kid to get back on heroin like I need a hole in my head. Interesting—sad I mean—that usage of the simile often implies that a hole in the head, administered by oneself, might be a reasonable response.

I’m thinking of that phrase because there’s a recently released documentary called Hole in the Head about Vertus Hardiman, a man who grew up in Lyles Station in southern Indiana, about ninety miles from where I’m writing this. Lyles Station was a town established by free blacks in the 1800s. It’s charming. I went there for a celebration day a few years back, paper plates of corn on the cob and baked beans and barbecue. We moseyed through the town museum and talked to locals.

I learned today, watching the trailer for that documentary, and with some subsequent online research, that when Hardiman was a boy in the 1920s, he was one of a group of little children, little test subjects, upon whom radiation experiments were performed. The experiments exposed these little children, little test subjects, to severe levels of radiation, such that, for little five-year-old Hardiman, it burned a hole in his head. (It might sound harsh to say it, but good lord, black people, never let an official-looking white person dressed in a white lab coat experiment on you or your children. Good lord.) If you’re like me, you’re picturing a scalp wound, like a cigarette or cigar burn. Maybe a peppering of them. Or you might even picture a patch of bald skin where the hair refuses to grow. Don’t picture that. Picture a fist-sized crevice in his skull, flesh and fat glistening as he removes the sock hat and bandages beneath, all the surrounding skin charred pink and gray.

I’m trying to remember the last day I haven’t been reminded of the inconceivable violence black people have endured in this country. When talking to my friend Kia about struggling with paranoia, she said, “You’d have to be crazy not to be paranoid as a black person in this country.”

Crazy not to think they want to put a hole in your head.

(Aug. 25)

6. Remission Still

I just got the sweetest textual message from my friend Walt. It read: “I love you breadfruit.” I don’t know the significance of this particular fruit, though I have recently learned that it is related to the mulberry, which is, unequivocally, among the most noble and delicious of fruits.

A few years back my friend Walt became intensely agoraphobic. He was afraid he’d be walking down the tree-lined streets near his house on Spring Garden Street and a bus would hop the curb and take him out. Or a limb rotted from the inside might drop on him from one of those trees. Or lightning. Or the earth itself might throw open its ravenous mouth—it happens—and gobble him up. Perhaps it’s no surprise that precisely seven years prior to the onset of this acute terror Walt was diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukemia, which, at the time, offered a seven-year survival rate, which actually means you have seven years to live. Seven years until you’re dead.

I remember the day Walt was diagnosed we were going to meet at Thai Lake in Chinatown for a late-night dinner, and he left a message on the answering machine that he’d had blood work at his checkup and his doctor sent him immediately to Hahnemann Hospital, where they made me wear a mask and booties to see him while they sucked his blood out of one arm, whirled it around in a machine, and put it back in his other arm in a stopgap measure called leukapheresis. He felt okay, but his white blood cells were a mess. His folks were there, looking nervous in their masks and gowns on a couch across the room. Walt’s already high-pitched laugh was a few notes higher, and a bit thinner, as he watched what was happening to his blood. When the treatment was done, he gave me his blessing to indulge at Thai Lake, to eat the Peking pork chops on his behalf, which I did, with the ong choi, most likely. It was, by now, about 1:00 a.m., and in that very full and loud and smoky restaurant I ate one of the loneliest meals of my life.

I went with Walt to get a second opinion from my uncle, an oncologist, who palpated Walt’s newly extra-lovable tummy and ran bloodwork, which returned the same results. “So, the survival rate is seven years,” Uncle Roy said. It must’ve been something like my father, whom Walt adored, telling him he’d be dead in seven years. And maybe it was something like me saying it. There I go, putting myself in the middle of everything. I guess I could just ask Walt.

Without getting too deep into the unabashed turmoil of interferon—someone should (not) do a Marina Abramovician performance by injecting this toxic drug, experiencing flu-like symptoms, et cetera—which was so severe, so awful, that after a two-week break from the poison keeping him alive, which the doctors call “a vacation” (beware anything called a vacation that isn’t actually a vacation), Walt, at the thought of going back on the stuff, walked his ass into the psych ward, lest he put a hole in his head. Walt needed to feel bad like he needed a hole in his head. Walt needed to feel better.

And so when a drug called Glivec was introduced about five years into Walt’s illness, it occasioned a kind of remission for a lot of people, Walt included. (It seems to work so well that it cures about half of the people. Walt might be one of them.) Despite that remission, when seven years had passed and, pre-Glivec, he was supposed to be dead, he got real scared he was going to die. Which he did not.

(Aug. 26)

7. Praying Mantis

There is a praying mantis on the empty pint glass someone left on one of the red outdoor tables at the café. Most days there’d probably be some shimmer of judgment at the asshole who didn’t pick up after him—yes, I’m assuming—self, but today I’m far more interested in the fact that said asshole’s depravity has created a gorgeous transparent stage for this beast to perform on, and so the asshole is a kind of executive producer of sorts, and I am indebted to . . . him. This mantis is pale, with a yellowish tint. It has six legs, which I learned in the eighth grade indicates insectness. One of these legs, or, more precisely, one of the four segments of one of these legs, is flipped over the lip of the glass—just this second it shat a tiny near-cylinder of grayish-brown scat on the rumpled napkin beneath the glass, jiggling its ass before emptying itself—as though hauling itself up, which it is not, given as it just pulled that leg up to its face, and, with its oddly mechanical mouth (I know, I know, indication of how divorced I am from the natural world to say an insect is like a machine; it’s the other way around, I know; get off my back), seemed to clean (nibble) the length of its . . . forearm. I mean the segment with wiry hair- looking things flecking the bottom. Now it’s nibbling its foot, or paw, and it replaced the thing on the lip of the glass. Its mouth keeps working, like it’s enjoying itself. Or like someone with no teeth.

This bug seems to be dancing—it kind of pounces on the four legs beneath its abdomen, bouncing and swaying, like it’s hearing a music I’m not yet tuned to. And, trying to tune in, I notice the swell and diminuendo of cicadas nearby, and another cricketish chirping just over in those forsythia. The mantis’s head rotates occasionally, sometimes seeming to follow my movement, its big bulbous eyes and filamentous antennae twisting, its little mouth opening and closing. Turns out this mantis has been my companion for the last twenty minutes, this whole break in my afternoon, edging closer to me, dancing, then scooting closer still. And when I sit back in my chair, the mantis pulls its head over the glass to see me (am I being egocentric?), swaying as it does so. Dancing. A woman in a floral pattern dress just walked by and the mantis turned its head—its heart-shaped head!—in her direction. And now back to looking at me, and slowly scooting down off its perch on the glass by rotating its body and walking down the glass, onto the table, and onto my book—When Women Were Birds by Terry Tempest Williams—on the edge of the r

ed table, half a foot from my chair. The creature rears up on its back legs, extending its arms like it’s looking for a hug. Like it wants, maybe, to dance with me.

A few years ago I was going to give a poetry reading at my friend Jeff’s farm, football fields of cockscomb and zinnia. You can only imagine the galaxies of bugs soaring above them, whirling and diving, butterflies and bees and dragonflies and ladybugs, and the birds come to feast on them, a whole wild and perfectly orchestrated symphony of pollination and predation. Walking through this I noticed a faint buzzing and crackling sound on the leaf of one of the thousands and thousands of zinnias. In this one, an orange navel blazing out toward a soft pink mane, a praying mantis stood in the sturdy crook of one of its leaves. I thought it was chirping or trying to fly until I got close to it and saw it was holding in its spiky mitts a large dragonfly, which buzzed and sputtered, its big translucent wings gleaming as the mantis ate its head.

(Aug. 29)

8. The Negreeting

It’s a lot of pressure to nod at every black person you see. That’s what I’m thinking, generously, sitting on a bench in an alley in Bloomington between the chocolate shop and farm-to-table and across the street from the e-cig store, where the sun warms the brick wall behind me as a guy I see around town who mostly never acknowledges me walks by, not acknowledging me. In this town, where the population of black people is scant, the labor of acknowledgment is itself scant. (There he goes again, sipping his cranberry Le Croix, sunglasses on, paying me no mind. I like his sneakers, red like mine, and thought maybe in addition to being American phenotypical kin we might also be consumer kin. What a loss.) Though maybe that’s not right, and I’m neglecting the significant emotional burden, the emotional labor, of needing—of feeling the need, or feeling the mandate—to nod at every black person you pass. Maybe my not-kin (mind you, I never expect white people to nod at me) was just rejecting the premise and the mandate. (Maybe he didn’t see you, you ask? He saw me. Maybe he thought you were Dominican? Same diff!)

I was recently in Vancouver where they clearly have some entirely different racial thing going on—all manner of brown types, some nonbrown, too—though fewer, I’m guessing, African American types. I was just walking around, making crude and generalized observations, forgive me. Anyway, for two days I don’t think I negreeted once—oh, I tried, at the Thai place, where a mixed family’s brown infant was babbling and not eating his food cutely, and his black father, more or less right next to me, mostly never once acknowledged my presence despite his child not taking his eyes off me and me making futile slightly pleadingly negreeting eyes at him. Maybe dad was jealous? I doubt it. Anyway, my neighbor’s non-negreeting felt in Canada almost like a non-non. He was eating his Thai food with his family and keeping this beautiful floppy afro’d child from sticking a chopstick up his nose.

(One of my father’s favorite stories, and, to me, one of his saddest, was when he was working the register at Red Barn in Youngstown and a black customer concluded his order with the word brother. My father replied, “My mother didn’t raise any fools.” It must’ve hurt the guy’s feelings, because my dad had to pull out his Louisville Slugger to quell the disagreement, so he said. It hurts my feelings.)

When I landed back in Denver, bereft of negreetings for my two days in Canada, I was immediately negreeted, again and again, five times in ten minutes, which felt comfortable and inviting and true. Felt like being held, in a way, and seen, in a way.

My friend Abdel has been writing a book about innocence, and I’m going to co-opt a touch of what he’s exploring—particularly the fact that innocence is an impossible state for black people in America who are, by virtue of this country’s fundamental beliefs, always presumed guilty. It’s not hard to get this. Read Michelle Alexander’s New Jim Crow. Or Devah Pager’s work about hiring practices showing that black men without a record receive job callbacks at a rate lower than white men previously convicted of felonies. Statistics about black kids being expelled from nursery and elementary schools. Police killing unarmed black people, sometimes children, and being acquitted.

If you’re black in this country you’re presumed guilty. Or, to come back to Abdel, who’s a schoolteacher and thinks a lot about children, you’re not allowed to be innocent. The eyes and heart of a nation are not avoidable things. The imagination of a country is not an avoidable thing. And the negreeting, back home, where we are mostly never seen, is a way of witnessing each other’s innocence—a way of saying, “I see your innocence.”

And my brother-not-brother ignoring me in his nice red kicks? Maybe he’s going a step further. Maybe he’s imagining a world—this one a street in Bloomington, Indiana—where his unions are not based on deprivation and terror. Not a huddling together. Maybe he’s refusing the premise of our un-innocence entirely and so feels no need to negreet. And in this way proclaims our innocence.

Maybe.

(Sep. 6)

9. The High-Five from Strangers, Etc.

Today I was wandering the square of the small Indiana town where I gave a poetry reading at the local college. (A feature of the small-town Midwest: a city-hallish building in the center, always with some sad statue trumpeting one war or another. This one had a guy in one of those not-very-protective-looking hats they called a helmet during WWI. He’s carrying, naturally, a gun. Jena Osman’s book Public Figures alerted me to the ubiquity of the gun, the weapon, in the hands of our statues. A delight I wish to now imagine and even impose, given that beneficent dictatorship [of one’s own life, anyway] is a delight, all new statues must have in their hands flowers or shovels or babies or seedlings or chinchillas—we could go on like this for a while. But never again—never ever—guns. I decree it, and also decree the removal of the already extant guns. Let the emptiness our war heroes carry be the metaphor for a while.) As I was finishing circling the square, I passed a storefront garage with huge Make America Great Again signs. It was a foreign auto repair shop, and inside were mostly Toyotas and Hondas.

I settled into the coffee shop (where, it seemed, every other black person in this town was [hiding], every one of them offering me some discreet version of the negreeting), took my notebooks out, and was reading over these delights, transcribing them into my computer.

And while I was working, headphones on, swaying to the new De La Soul record (delight, which deserves its own entry), I noticed a white girl—she looked fifteen, but could’ve been, I suppose, a college student—standing next to me with her hand raised. I looked up, confused, pulled my headphones back, and she said, like a coach or something, “Working on your paper?! Good job to you! High five!” And you better believe I high-fived that child in her preripped Def Leppard shirt and her itty-bitty Doc Martens. For I love, I delight in, unequivocally pleasant public physical interactions with strangers. What constitutes pleasant, it’s no secret, is informed by my large-ish, male, and cisgender body, a body that is also large-ish, male, cisgender, and not white. In other words, the pleasant, the delightful, are not universal. We all should understand this by now.

A few months ago, walking down the street in Umbertide, in Italy, a trash truck pulled up beside me and the guy in the passenger’s seat yelled something I didn’t understand. I said, “Como,” the Spanish word for “come again,” which is a ridiculous thing to say because even if he had come again I wouldn’t have understood him. He knew this, and hopping out of the truck to dump in a couple cans, he flexed his muscles, pointed at me, and smacked my biceps hard. Twice! I loved him! Or when a waitress puts her hand on my shoulder. (Forget it if she calls me honey. Baby even better.) Or someone scooting by puts their hand on my back. The handshake. The hug. I love them both.

Once I was getting on a plane, and shuffling down the aisle I saw, sitting at the front of coach, reading a magazine, my great-uncle Earl. I got down on my knees and put my hand on his forearm and said, “Uncle Earl! It’s me, Ross!” He looked at me kind of quizzically, as did the woman traveling with him who did not look one bit like

my Aunt Sylvia, which made me look back at my not-Uncle Earl who looked maybe like my Uncle Earl’s second cousin twenty years ago. And though it was benign, and no one was hurt, it was a little weird, and they looked confused. All the same, given as Uncle Earl died about six months later, I’m delighted I got to see him, and touch him, gently, lovingly, about one thousand miles away.

(Sep. 9)

10. Writing by Hand

I love the story, apocryphal or not, of Derek Walcott asking his graduate poetry workshop on the first day if they composed by hand or on a computer. As I recall, about half of the class raised their hands when he said computer. I didn’t know him, but I did sit in on a workshop he led in college shortly after he won the Nobel Prize and I was both mesmerized and a touch terrified by his mellifluous and curt voice, lilting like a beach rose, all fragrant and thorny. He said, with almost no affect (which is itself an affect), “You six can leave my workshop.” And just like you would’ve, they gathered their things and started down the hall, probably wondering if Pinsky had any seats open in his class. Before they got too far though he called them back—the fragrant part of the rose—“C’mon, c’mon, I’m just making a point.” What was the point?

Susan Sontag said somewhere something like any technology that slows us down in our writing rather than speeding us up is the one we ought to use. Her treatise on the subject, long-handist that she evidently was. (I wonder if the speed they all gobbled in the sixties and seventies counts as a technology.) And though I don’t have any particular treatise, I do want to acknowledge that writing by hand, and writing these essayettes by hand in particular, has been a surprising and utter delight. Mind you, I would not have been tossed from Walcott’s workshop, because I write poems pretty slowly, line by line, with a pen, a Le Pen these days (a delight, the Le Pen is).

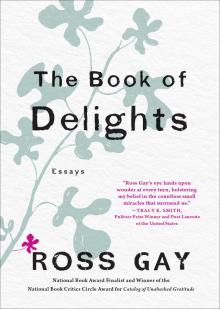

The Book of Delights

The Book of Delights